Heart to Heart with Anna

Revitalize your spirit and connect with the vibrant congenital heart defect (CHD) community through 'Heart to Heart with Anna,' the pioneering podcast that has been inspiring and informing listeners since 11-12-13. Join us as we dive deep into the personal journeys, triumphs, and challenges of Survivors, their loved ones, esteemed medical professionals, and other remarkable individuals within the CHD community.

With unwavering dedication, our heartfelt conversations bring to light the stories that need to be heard. Gain invaluable insights, expert advice, and a sense of empowerment as we explore the multifaceted world of CHD. Our mission is to uplift, educate, and enrich the lives of every member of this incredible community.

Embark on a transformative listening experience where compassion and understanding thrive. Discover the resilience and unwavering spirit that resides within each person touched by CHD. Together, let's build a community where support and knowledge flourish, bringing hope to the forefront.

Tune in to 'Heart to Heart with Anna' and embark on a remarkable journey that will leave you inspired, enlightened, and connected to the beating heart of the CHD community.

Heart to Heart with Anna

An Author for CHD Adults with Learning Disabilities: Deanna Altomara

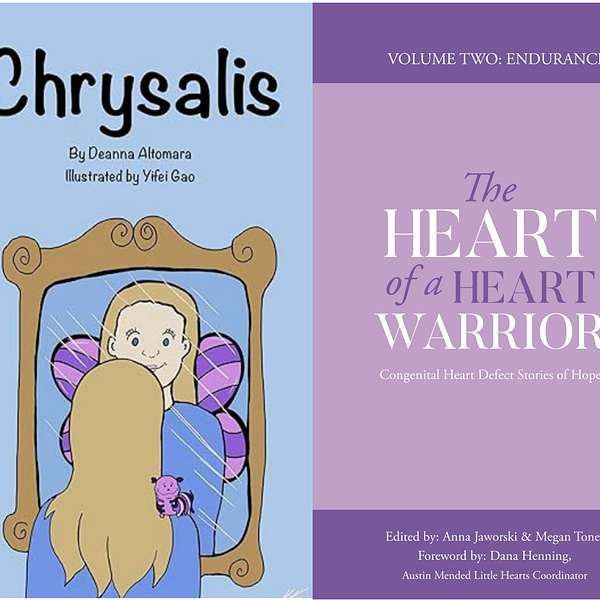

As an author myself, I understand the power of stories to heal and inspire. That's why I'm thrilled to introduce Deanna Altomara, who created "Chrysalis," a book to help people facing open-heart surgery. Born with a congenital heart defect herself, Deanna understands what it means to have had open-heart surgery. Deanna's tale is a testament to how health education and storytelling can intertwine to provide solace and strength to those facing similar battles.

Navigating the complex maze of medical procedures and developmental disabilities can be daunting for teens and their families, but this episode illuminates a path of understanding. It was essential for Deanna to create a book for her cousin, who was born with a heart defect and who also deals with developmental disabilities. We delve into the meticulous creation of age-appropriate resources that educate and resonate, merging factual information with fun. Discover how collaboration with an illustrator brought forth a book that captivates without patronizing, and how such tailored storytelling can touch the hearts of its readers and bridge significant gaps in resources.

Rounding out our heartfelt talk, we share insights into the creation of indispensable tools that guide parents through the intricacies of surgeries and special needs.

In the third segment of the podcast, you'll hear my co-editor Megan Tones and me, as we continue reading from The Heart of a Heart Warrior Volume Two Endurance. This week, we cover the first half of Chapter 7 which includes David Franco's harrowing recovery journey which underscores the essence of resilience. This chapter is entitled "Facing My Mortality" and you'll hear essays by Becca Atherton as she confronts life's fragility and her impending mortality. We also hear from Margaret Raymond as she describes how her mental health has been challenged over time due to living with her congenital heart defects. Despite the inevitable, we find a collective strength in this chapter.

Join our supportive community, where every Tuesday, we offer a dose of inspiration and the comforting reminder that no one walks this path alone.

You can find Deanna on @d.scribing.stories on Instagram and https://deannaaltomara.com

To sign up for a Baby Hearts Press Book Study, visit our website here: https://www.babyheartspress.com/volume-2

A bi-monthly podcast where we share the stories of our Caregivers, patients and...

Listen on: Apple Podcasts Spotify

Anna's Buzzsprout Affiliate Link

Baby Blue Sound Collective

Social Media Pages:

Apple Podcasts

Facebook

Instagram

MeWe

Twitter

YouTube

Website

When my cousin, who has a developmental disability, was told that she needed to have open heart surgery, I immediately knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to make her a book that would help her, just like Grover had helped me.

Speaker 2:Welcome to Heart to Heart with Anna.

Speaker 2:I am Anna Jaworski and your host. I'm also a heart mom to an adult who was born with a single ventricle heart and who is 29 years old. That's the reason I am the host of your program. With me today is Deanna Altamira. Deanna is a lifelong reader who has combined her passion for science and storytelling by double majoring in human health and creative writing at Emory University. She continued her studies at Rollins School of Public Health, where she earned a master's in behavior, social and health education sciences and a certificate in climate health. She is here with me today because she has written a book called Chrysalis, which is a children's book specifically for the congenital birth defect community. Deanna is especially qualified to write this book since she has had open heart surgery herself. As a member of the zipper club, she understands firsthand the importance of empowering a child when having surgery. You can find Deanna on Describing Stories on Instagram and DeannaAltamiracom, and I'll have those links in my show notes as well. So if you're riding your bike or you're out on a run, don't worry about it. You can just look in the show notes and it'll be there.

Speaker 2:After our interview, Megan Tones and I will take turns reading from chapter seven of the Heart of a Heart Warrior. You can sign up to take part in a book study of volume two, which is where chapter seven is, by visiting my website, babyheartspresscom. We will be discussing the book on Thursdays from 5 pm to 6 pm, USA Central Time. We'll discuss the book for the first three weeks and then on the fourth week, we play a Jeopardy game, which is so much fun and people get a chance to win prizes. All questions for this one will be based on volume two and what we discussed in the book study session. So it behooves you to attend all of the book study sessions. It's only $10 a session and I'm limiting it to 12 participants so everybody has a chance to share in the discussion, and the Volume 2 Book Study Session starts on March 21st, which is World Dance and Dream Day.

Speaker 2:Now on to the show. Welcome to Heart to Heart with Deanna. Deanna, hey, thank you for having me, Deanna. I had to have you on the show when I saw a special note by you on my Instagram account. So thank you for telling me about your book, Chrysalis, and I downloaded it from Amazon. It's so adorable. Can you tell me why you wrote your book and who you intended the book for.

Speaker 1:Yeah, it's kind of a long story.

Speaker 1:That starts when I was about a toddler and I had heart surgery and one of the earliest things I can remember is my mom reading me the book Rover Goes to the Hospital.

Speaker 1:It's about the Muppets character who has to get his tonsils taken out and he goes to the hospital and he meets the nurses, he tries on the gown, he sees the little bracelet and it's just to help him get more comfortable with the idea of going to the hospital and what's going to happen there. So sitting on my mom's lap reading that is something that, looking back, has been extremely formative for me and growing up it really helped me with coming to terms with the surgery I'd had and why I had the scar and my friends didn't, and understand that it's okay. You know, everyone goes to the doctor and gets help, sometimes so fast forward I fell in love with reading and writing even more as I grew up and I continued to get really involved in health education and health communication in a more scholastic way as well. So when my cousin, who has a developmental disability, was told that she needed to have open heart surgery, I immediately knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to make her a book that would help her, just like Grover had helped me.

Speaker 2:That's so sweet, that is so sweet.

Speaker 1:It was something that I was really excited about.

Speaker 2:Yeah, you saw the deed. And it's funny that you said what you did about the Grover book, because I remember when my child was young, I was looking for a book for my older son, joey, who was three years old, and I couldn't find anything for siblings. The only book I could find that was of any relevance was Grover going to the hospital and having an operation, but there was nothing there for the brothers and sisters left behind. So that's why I wrote my book. My Brother Needs an Operation.

Speaker 1:And I saw a very similar need.

Speaker 1:I recently did a project on books that are about disabled characters for middle school students, and that included doing some research on what's out there for elementary school students, because at the time I did this project last year, there was no information on books you could get about disabilities that were fiction for middle school students.

Speaker 1:The only things around were books for toddlers and preschoolers all about acceptance. It's so fascinating the gaps that we still have in that area. But also more pertinent to this is the fact that my cousin, who I wanted to write this book for, she was not a baby, she was a teenager at the time and I did not want to give her a book written for a baby. Sure, right, yeah, and having the developmental disability, I wanted to write something that would be perfect for her, suit her reading level, suit her interest. So I talked with her, I talked with her mom and I wrote this story that was all about Kaylee and this adventure that Kaylee could refer back to to help her understand what was going to happen in the hospital every step of the way, how she would be supported every step of the way, and to get that more fantastical element in there by this fable, the caterpillar, that she reads, uh, so that was.

Speaker 2:I love that. That's so sweet and it shows what a special relationship you must have with your cousin.

Speaker 1:Yeah, Now did she know that you were going to do.

Speaker 2:I'm sorry. Did she know that you were going to do this or did you surprise her when it was done?

Speaker 1:She knew. I talked more with her mom about what the procedure would be like and what the specifics of her situation would be, especially because my operation had been so long ago. Yeah, yeah, things have changed and things have changed. A lot of things have changed. And also what I remember is what a three-year-old would remember and not what would be practical information for a teenager who wants to learn about a surgery would be. So I do a lot of research on the Internet about what is currently being done and what is the status quo for that, and also the latest on coping skills and educational techniques to help people understand what is going on in different ways and how to structure information so that it sticks. So I was able to do a lot of research in that regard and then I had it all ready for Kaylee before her surgery and she read it and she loved it and she said it really helped her and I know she still reads it sometimes for fun.

Speaker 1:So that makes me really happy inside to know that it had that impact on her and afterwards exactly, exactly, and afterwards I thought to myself that if this book had been so helpful for her, maybe it could help other kids too. So I went back to the original draft and I made it a couple tweets to make it a bit more focused on a more general audience and also to incorporate more of the things that I had continued to learn about public health and health communications. And, based on those tweets, is what I published and you can now get online.

Speaker 2:That's amazing. Did you hire an illustrator?

Speaker 1:I did. I got some grant funding through my school and I was able to work with a fellow student who does illustration. Her name is Yifei Gao. She talked to me on the phone many times in person and I relayed information between her and my cousin. I was very involved with checking things back and forth with my cousin and her like, what color does Kaylee want the butterfly to be? Going back and forth to make sure things were perfect, and she did a really beautiful job on the pictures, as you can tell.

Speaker 2:She did do a good job. It's very fanciful, I guess is the word I would use fanciful and it's fun. However, like you said, it's not babyish. It's fun. However, like you said, it's not babyish, so I can see where even a teenager might enjoy that, especially a teenager who has some learning disabilities. I think you did a really nice job there of making it fun but not babyish.

Speaker 1:I hope so, because I don't want to hand a teenager a book that looks like it's for a little kid. I intentionally made it so that it's a chapter book format and it doesn't have illustrations that look babyish. It still has some illustrations to help brighten it up and make it more exciting and emotional, but it is meant to be something that a teenager, especially a teenager with developmental disabilities, can really enjoy and feel good about reading.

Speaker 2:Yeah, absolutely, I love it. It just came out recently, or you just told me about it recently.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I first wrote it for her a couple years ago, and then a year ago is when I published the paperback version, and just a week or two ago I released the e-book version on Kindle.

Speaker 2:I wrote a review, and I guess I hadn't written a review in a little while, so to my great surprise, I don't remember doing this. But I must have attached my Goodreads account to my Amazon account, so it went out on both platforms, which is kind of cool.

Speaker 1:That is really cool.

Speaker 2:Yeah. So, friends, if you want to write a review of any of our books, my books included please, please, go out to Amazon, connect your Goodreads account and then you can write one review and it will show up in multiple places. It really does help people like us who are looking for these very specialized type of books. Sometimes it's hard to find them because these are probably not going to be on the New York Times bestsellers list. So when you do a search in Amazon, there are a lot of other books that may pop up before ours. Do a search in Amazon there are a lot of other books that may pop up before ours. But the more reviews we have, the higher it ranks us and then the book is seen more easily. So keep that in mind Really does help. Even if you only write a sentence or two sentences, the fact that you take the time to rate it and let people know if you enjoyed it really does make a difference for us authors.

Speaker 1:A good review makes my day Me too, exactly as a writer. Oftentimes you put your heart and soul into something and send it out in the world, and then it just crickets. You're like I really hope someone liked it, I know.

Speaker 2:And you hate to ask everyone you know, would you please write a review of my book? But you really need those reviews to help people find your book and to be able to make a difference. And you're like me. This is a passion project. This is something you did because you saw a need that wasn't being fulfilled in the traditional realm of books that's out there, Even though there are millions of books out there, it's not out there. The one that you want is not out there.

Speaker 2:So you took it upon yourself to do that research, to write, to find an illustrator. I mean, this kind of project it does not happen overnight, friends. It's a lengthy process and then, when you go from okay, I'm going to do a printed book, and now I'm going to do an ebook, you would think, oh, all I have to do is flip one switch. But that's not what happens, because there are gremlins in the computers. There are gremlins between going from your computer to Amazon or your computer to Ingram. It is amazing how many things can get messed up and require editing, proofreading. All that stuff that you had to do for the printed book, you have to do it all over again for the ebook. It's not a simple process. It's not hard, but it's not simple either. I don't know if that makes sense. It's like you can do it, but it's very time consuming, Wouldn't you say, Deanna?

Speaker 1:Yes, it is crazy because there are certain things in Word I know how to do inside out, but when I sit down to do them, Word has a fit and for some reason it's not working. And you're Googling, and you're finding the directions and you're 10 pages into the Google results and you're like I literally am clicking the exact button they're telling you to click, but those remnants that's a great way to put it.

Speaker 2:They're telling you to click, but those remnants that's a great way to put it oh my gosh. And you have the same issue that I have, which is we have a book that has text and illustrations, or text and photos, and they make it sound like, oh, if you just put everything in a PDF, you can just upload that to Amazon. Well, forget about it. When I tried to do that, you can just upload that to Amazon. Well, forget about it. When I tried to do that, all the pictures went on top of my text and I just had a devil of a time. So, yeah, it's not as easy as you think, friends. So please be kind to your friends who are authors and give us a review. We really appreciate it.

Speaker 2:So I'm not going to belabor that anymore, just want everybody to know you need to love on your authors, because it is a tough and very solitary occupation. I mean, the tagline for this podcast, as many of you know if you've listened to any episodes, is you are not alone. But when you are an author and you are sitting in front of your computer and there is nobody else around, it can feel very isolated and, like Deanna said, you put it out in the world and you're hoping that this labor of love helps somebody, and then it's not uncommon to not hear anything. And you wonder did I do anybody a service? Was this something people found helpful? And you hope it is. But unless you get some kind of feedback, it can be very sad. It's just sad for us.

Speaker 2:This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. The opinions expressed in the podcast are not those of Hearts Unite the Globe, but of the hosts and guests, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to congenital heart disease or bereavement.

Speaker 4:You are listening to Heart to Heart with Anna. If you have a question or comment that you would like addressed on our show, please send an email to Anna Jaworski at Anna at hearttoheartwithannacom. That's Anna at hearttoheartwithannacom. Now back to Heart to Heart with Anna.

Speaker 2:You have a ton of helpful information at the end of your book. That is for parents, but you were only three years old when you had your surgeries. Tell me exactly how you came up with these checklists to make them helpful for others who are reading your book.

Speaker 1:I talked to my mom and my aunt extensively about what I had went through and what my cousin was going to go through and started from there. But when I was making the revisions to the book to publish it, I went through a process of more in-depth research that included a lot of internet surfing, first of all to see what tips were available online. That would be the most helpful. But, even more importantly, I reached out to people who were already in the heart community, in the special needs community, and did interviews and did surveys and talked to them about what happened with you and what would you recommend for people who are going through it in the future, and that really gave me a lot of helpful information about it from all different perspectives, from parents, from teachers, from people in the healthcare fields. That really informed what types of things I would include in the book and also include in the sections afterward.

Speaker 1:Even the checklist was suggested by someone and it makes total sense because, as you look at behavioral health theory, it is so helpful to have a checklist with solid list of actions that you can check off. It just makes it so much easier for people to put something from words into reality when you have it put in that format. For some reason, that's just what our brain loves, and that's especially true for a lot of people with special needs like autism, where behavior and thinking is very regimented. I used to work at a camp for kids of autism. Life was structured by the schedule and first we did this, now we're going to do that, and then we're going to do this, and it just helps things go so much more smoothly when you have a schedule, knowing exactly what to expect, like okay, I took my medicine, in a few hours, I'm going to eat lunch and then I'm going to do my physical therapy exercise. It's just having that structure is super helpful for a lot of people.

Speaker 2:Absolutely, and I would go so far as to say, when you are a parent and you think you're having a perfectly healthy baby and then all of a sudden you deliver a baby and it's whisked away to the NICU right away, it's overwhelming, it's frightening. And then you're told oh, your child's going to need three surgeries. If you have a kid who's got a single ventricle heart, and so that first surgery, those babies don't remember that because they usually have that within the first year of life. So they don't remember that. But then they may have one as a toddler and that may be one that they do remember.

Speaker 2:So having a book like this doesn't just help the child, but it also helps the parent and it allows you to do something that I was very careful to do with my child. You to do something that I was very careful to do with my child, which was I had my child home for two months before we discovered what was wrong. So I had already developed a routine with my baby when we got put in the hospital with that open heart surgery. I tried as best I could to keep to that routine. So when I took my baby home it wasn't difficult to get back into that routine again because I had been using that in the hospital. A resource guide like this helps the parent to know oh, I have to account for physical therapy, I have to account for blood draws, I have to account for different things that are going to interrupt a child's normal routine. But they can take that into account when they're developing a routine and when they get home it can help inform their new routines.

Speaker 1:Exactly. And it was kind of hard doing that for such a broad audience because every kid is going to have a different experience and a different routine. Some will have certain physical therapy exercises, some won't. So I tried to be more broad when I was writing it and saying like oh, meals will be brought three times a day, physical therapy will happen when my doctor tells me. And I gave extra boxes so they could write other things in there and drew extra columns where they could have a picture or a sticker to help them visualize, because it really is just so unique.

Speaker 2:I think it will. When I saw it, I thought, wow, that would be so good. I used to be a special education teacher and I worked with children who needed communication boards and something like this you could fit right into that, where you could even put pictures of the therapist or the room that they're going to or something like that, and it would help them to identify what's coming next.

Speaker 1:So they're not caught off guard.

Speaker 2:Yeah, because kids like that. If they know what's coming up, then generally they'll be more okay with it than if all of a sudden they're surprised with something. And that's when you can sometimes see problems with behavior, or you can see kids just shut down because they're overwhelmed.

Speaker 1:Mm-hmm, or they're anxious, so those boards were very inspirational when I was doing this.

Speaker 2:Absolutely, that's wonderful, very inspirational when I was doing this. Absolutely, that's wonderful. Well, deanna, there are quite a few adults with Cajetal heart defects who have reached out to me and said I'm going to write a book. What advice would you give somebody who was born with a heart defect who wants to?

Speaker 1:become a writer, I would say think about what your story is and what that story means to you and what you can give from it to other people. And, starting from there, and just start with what feels right to you, even if it doesn't make its way into the finished book. 50 pages of scribbled notes and margins can be extremely therapeutic, just to figure out.

Speaker 1:It can, it can and you know there are so many things that I don't realize until I've written 50 pages of junk where I'm like, oh, there is a trend here and I did not notice that before. But now that I've noticed that even though I'm not going to actually publish this 50 pages of junk I just wrote, now I've got this golden thread that I can use to map out my story more fully. So I think that's a helpful way to approach it.

Speaker 2:That is a helpful way to approach it and it's funny because I was just in a course that I am taking and they called it a red thread. You called it a golden thread, but they called it a red thread. Same concept but when you're working on speech writing. So many of you may know that, aside from being a podcaster, I'm also a public speaker.

Speaker 2:I speak at conferences and wherever parents are gathered. You can find me there at times telling stories and sharing information, and it does help to have that one theme or that one thread that goes through and unifies your message. So I think that's beautiful. Don't be afraid to spend hours writing and let it all out and then maybe just let it go and allow that to be where you find that thread and where you feel that you can have the most impact in the world, because that's a hard thing, I think. Whittling down to the main focus, that's what a lot of people have trouble with and they get overwhelmed because they feel like they have to say everything and you don't. You can focus on just one aspect of your life and share that story. A lot of times it can be big enough to become a book, even if it is just a book for kids.

Speaker 1:Exactly, and it's so interesting, sometimes just serendipitously, what pops up. I was applying to graduate school at the same time I was working on this book for Kaylee. So I'm sitting there banging my head what am I going to write my essay about? And I wanted to study health communication. So we're trying to think back to the very basics, like why do I like health communications? What got me interested in it in the first place? I'm not really sure I remember loving reading from a young age and then I looked over and saw my document for Kaylee and I'm like holy cow from a young age, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2:It's been my life story. Yes, oh wow. I bet your essay was amazing for college. Thanks. Did you get accepted by the college that you wrote that for?

Speaker 1:Yeah, well, that's awesome.

Speaker 2:I love that. Oh my gosh, this has been completely delightful. Thank you so much for coming on the program today.

Speaker 1:And thank you so much for having me. It's been such a pleasure.

Speaker 2:Oh, it's been so much fun. Well, friends, that does conclude the interview portion of this podcast. We'll take a short break and when we come back you'll have a chance to hear my co-editor, megan Tones, and me read from our new book the Heart of a Heart Warrior, volume 2, endurance Today the Heart of a Heart Warrior.

Speaker 4:Volume 2, endurance. Today you'll hear us read the first half of Chapter 7. Heart to Heart with Anna is a presentation of Hearts Unite the Globe and is part of the Hug Podcast Network. Hearts Unite the Globe is a non-profit organization devoted to providing resources to the congenital heart defect community to uplift, empower and enrich the lives of our community members. If you would like access to free resources pertaining to the CHD community, please visit our website at wwwcongenitalheartdefectscom for information about CHD, the hospitals that treat children with CHD, summer camps for CHD survivors and much, much more.

Speaker 3:Chapter 7. Facing my Mortality. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this intro was the hardest for me to write. Even now, as I am sitting captive on a train, I am struggling with the elephant in the heart chamber. So often we are celebrated as resilient, brave and strong that it's hard to acknowledge that we might feel the opposite. Like many of you, I have had brushes with my mortality and it's never not frightening. I lay in my little white bed in coronary care, my heart rate at 170 again. These episodes were becoming a familiar occurrence, to the point where they bored me A commercial break in life, waiting in line for the roller coaster Aeon. At least this ward had free television.

Speaker 3:My nurse for that evening was a friendly middle-aged man we'll call him Gordon, who enjoyed chatting. I was happy to pass the time waiting for the CHG specialist to prescribe an infusion of a notorious anti-arrhythmic so I could get out of there. Gordon looked at the game show I was watching and pointed to one of the contestants. I remember that man. He used to have a TV show where he pranked people. Then somebody was killed and he could never bring himself to work on TV again.

Speaker 3:After dinner my family came to visit and thankfully so did the doctors. They attached the bag of medicine to my IV. I cannot explain, but like Han Solo, I had a bad feeling about this. Could you just stay, I said to my husband and Gordon. Within seconds I felt cold, like a venomous snake had bitten me. So far, so good. Then I felt nauseous. Uh-oh. I breathed out and inhaled what felt like wet cement and stopped breathing. I looked across and glimpsed my heart and oxygen saturation rates dropping rapidly. Everything turned to melting stained glass. The last thing I saw was Gordon pushing the emergency button. I'm going to feel bad for him if I die. Two white blobs appeared and pulled the brown blob that was my husband in his winter coat out of the room. Then a white blob pulled the IV out of my arm and put a bag of oxygen on me and I started to breathe again. To this day I have no idea why that happened.

Speaker 3:My lungs crackled for weeks and I scheduled a much-needed ablation to get off some of my medication. Mentally it was rough. That day had started off great. It was a beautiful sunny day and I took the dogs to the park. Then at around 8pm I was almost dead. The thought that I would have to go back to work seemed absurd. Could you imagine Rambo working in an office? Somehow I did fine for a few years. Then cracks started to appear in my early 30s. I remember doing things like going to work in my pyjamas and getting dressed when I got there, or breaking down in the car park in a shopping center, which is especially embarrassing when you don't have a car. Those incidents and war prompted me to see a psychologist, which was a helpful start. My experience is just one of many.

Speaker 3:Mental health problems are something many of us face, whether it's trauma from medical and other adverse experiences underlying neurodevelopmental conditions or just our genes twisting the knife that bit more and giving us a side of psychosis with our cyanosis. Sorry, I couldn't help myself. This chapter will be a hard read, but I feel it's important to witness the raw honesty of the authors as they describe the role mortality played in their lives. David Franco's adult life was just beginning when he had a stroke during a valve replacement surgery, forcing him to adapt to a new normal. Margaret Raymond talks about her personal experiences of trauma, the impact it had on her development, growing up and receiving care as an adult, and how she cares for her mental health.

Speaker 3:Baker Atherton's pieces Car Ride Home and you Can't Even Imagine perfectly capture the desolation and anticipatory grief of losing control of one's body and life and having to face the prospect of dying young. Travis Martin's essay is about how he found his way back to a healthy lifestyle after years of partying in college left him overweight and facing a kidney transplant. His essay shows that, even though having CHD is beyond our control, we have the power to make decisions about our lifestyle that can improve our health. Lauren Elizabeth's poem Clear is about the power of faith when facing medical crises. Leslie Castro-Dupman's Dear Heart is a farewell to the heart she was born with, written in the hours prior to her heart transplant. Finally, michael Montgomery's piece describes the visceral experience of being in the operating theatre prior to being put under for surgery, an experience which was exceptionally jarring for him as his CHD had made itself known earlier that day on the football field, itself known earlier that day on the football field. Thank you for reading this chapter, which brings the shadow CHD casts on us into the light.

Speaker 2:It's not just the age, it's the mileage by David Franco. I can't see. Terror gripped me as I opened my eyes but couldn't see anything beyond flashing points of light. What was worse than that was that nobody believed me. I sank back on the bed. How in the world did I get here? Just a little over two months earlier I had gotten married. It was a great time in my life. Working at the Texas Lottery was a challenging job that meant I had health insurance and other great benefits. As a hotline supervisor for the brand new lottery program, I had learned enough to be sent to Atlanta to help Georgia set up its own lottery.

Speaker 2:One day after work I hopped in my car and headed to yet another cardiology appointment. The cardiologist put his icy stethoscope on my chest and listened intently, saying little. He moved around and put it on my back. Take a deep breath, he instructed me, david. The cardiologist had said I think it's time, but let's do a transesophageal echo to make sure. I'm hearing a whooshing sound that makes me concerned about your pulmonary valve.

Speaker 2:At 27 years of age, it was almost inevitable. I was born with a complex heart condition called congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries, or CCTGA for short. I had only had one open-heart surgery, but by 27 years of age I figured I was due. In my younger days, things were different. At that time, patients smoked in our hospital beds. Even though I was a kid, I was almost always on an adult floor where all the heart patients received care. Rooms had windows you could open and everything had that hospital smell stale cigarette smell, mixed with disinfectant that smelled more like an infectant. It's time to replace your pacemaker. Those were words spoken to me over and over again, making the hospital my home away from home.

Speaker 2:At 27 years of age, I was able to make decisions for my health care myself. I know where I need to go. I informed a cardiologist. There was no doubt in my mind. My first open-heart surgery was done in 1972 in Alabama, and the assistant surgeon for that surgery was now the surgeon who would do my procedure. I passed pumpkins, ghosts and mocked tombstones.

Speaker 2:As I drove to the hospital, a few hospital employees were dressed up in costumes. Son, did you bring your blue suede shoes with you? An Elvis impersonator asked me as I signed into the hospital. I just smiled and thought back to the conversation I had had with my new bride. Don't worry, I assured her I've been down this road before. It's not my first rodeo.

Speaker 2:Pam looked at me wide-eyed with concern Do you need me to go with you? I've been through all of this before I remember telling her. Look, it's pretty simple. They're going to take out my pulmonary valve and replace it with a porcine or pig valve. The whole surgery should be six hours tops. I'll probably be there for 10, and then I'll be home again Good as new no better than new, because I'll have a brand new pacemaker inserted too. Mom is going to meet me at the hospital. We've got this.

Speaker 2:Preliminary tests were done. They admitted me to the hospital. Everything was going according to plan until it wasn't they deemed my heart surgery a success. Mom wasn't allowed in the cardiac ICU. We're having a little trouble waking David up, she was told.

Speaker 2:Although not comatose, I couldn't seem to wake up. I don't remember any of that. I felt the stiff hospital sheets on my body and my brain groggily remembered where I was. Wake up, I said to myself. I could hear the machines hooked up to me making their typical noises. My bed was near the window and I could feel the heat of the sun falling on me.

Speaker 2:But when I opened my eyes, nothing. My tongue felt too big for my mouth and I could hardly speak. I can't see. I wanted to shout. In response, I struggled and pulled out all the IVs. The EKG electrodes popped off as I struggled against the sheets and blanket. I need to get out of here. I thought I want to go home. It's okay, david. Mom was saying, while she and the nurses tried to restrain me. David, stop, mom, begged me. Time had no meaning. While I blindly clung to the hope that my sight would return, closing my eyes, I couldn't believe this was happening to me. In the quiet of the night, I could feel my mother's presence and knew she would be saying a rosary for me. I knew God was with me, but I felt forsaken at this dreadful time.

Speaker 2:Mom, I said hoarsely I see dancing lights. Pam, you need to get here now. My mom said to my new wife from a telephone. In the hallway, nurses changed shifts, doctors came and went. Finally, my wife and my mother were by my side. What's your name? What year is it? Who's the president of the United States? I answered in a slurry and shaking voice David Franco. The year is 1958, and the president is Dwight Eisenhower. The year was wrong, but I knew who the president was in 1958.

Speaker 2:He's having trouble with his entire right side, said the nurse to a doctor. I think he's had a stroke. Mom, where's Pam? I remember asking. I'm here, she said, but I couldn't see her until she was directly in front of me. I felt so alone. Would I ever feel like myself again? We're going to order a series of tests. The doctor informed us. We need a spinal tap, an electroencephalogram, eeg and a head CAT scan. There's nothing really wrong with David, the neurologist said. His brain activity is a little slow, but otherwise I can't find anything wrong. Where is the cardiologist? Pam asked. He had to go to a conference after David's surgery. Mom replied.

Speaker 2:I sank into the bed feeling more alone than I ever remember, feeling I couldn't see. I could barely move. I knew my speech was slurred. I've had a stroke. I thought to myself Nurse Farrell is right. Why won't anyone listen to us? He's just having an adverse reaction to the anesthesia.

Speaker 2:I overheard someone saying I think he's a malingerer. A cardiologist said I knew what they were saying and thinking they thought I didn't want to recover. Were they crazy? How many more tests are you going to give him? Pam asked after I'd already failed the strength test, the cognitive test, the coordination test and the gait test. We can't figure out what's wrong. She was told. Let's go ahead and replace your pacemaker.

Speaker 2:A doctor said about a week after my valve surgery how can time move at a snail's pace and yet go by so quickly? It's finally time to go home. Pam informed me it had been three weeks, not the 10 days I had prepared her for. You'll get cardiac rehab at home, david. Mom said You're going to get better, david. We believe you've had a stroke and we're going to do everything we can to help you, I was told.

Speaker 2:At rehab they saved my life in so many ways Occupational therapy, speech therapy, physical therapy and visual therapy all focused on getting me back to who I was before they replaced the valve. It was the cognitive therapy that was the biggest lingering problem after the stroke. I can't play the guitar. I said to mom on the phone one day. The stroke I can't play the guitar. I said to mom on the phone one day my right hand just doesn't want to do what I know it can do. Relearning how to play the guitar became one therapy that helped me find myself again.

Speaker 2:I find it is the small things that seem to bother me in life. I'm so upset at all my losses and changes and capabilities. However, I'm still very much alive. I became a different person in so many ways. I don't know what I would have done without you. I said to Dr Harris, the man who diagnosed my stroke. Without you and my cognitive therapist, ruth Ann Curtis, I wouldn't be where I am today. He brushed aside my praise. But I'm introspective. I realize I probably wouldn't still be married to my wife of 25 years. I doubt I would be able to drive, play the guitar or raise my daughter into adulthood. Looking back on everything that has happened to me in my life, I realize it's not the years we live that matter. It's what we do with the time we have. I've learned to appreciate my daughter's laughter, the warm Texas sunshine on my back when I'm barbecuing, jamming on my guitar, or even sitting alone with my cat Thomas while we work together on my computer. Additionally, there's the joy of witnessing another Corpus Christi sunset with my dog Douglas and my daughter Sarah, after visiting her at college following yet another cardiology appointment.

Speaker 2:David Franco was born on December 19, 1966. He grew up in Hastings-on-Hudson, new York. David was father to Sarah and he was a very hands-on stay-at-home dad. He was a fur father to his cat Thomas and his dog Douglas. David was also a co-host for the podcast Heart to Heart with Nicole and David and he volunteered with Hearts Unite the Globe as a sound engineer, a producer and wherever else he was needed. David was a devout Catholic and he was an accomplished guitarist. He often took his guitar to CHD conferences where he would jam with anyone willing. He was a big CHD activist and he took part in various fundraising projects to raise money and awareness of CHDs. Editor's Note Sadly, david passed away on March 12, 2020, from complications related to his CHD. He was in the dog park with his constant companion, douglas, by his side. Car.

Speaker 3:Ride Home by Becca Atherton. My head was pressed against the cold car window as I watched the world blur together. My head was pounding, probably from the sinus infection, but the fears that were crammed into my mind didn't help any. Your lung function is down 20%. I squeezed my eyes shut, trying to forget what Dr Conrad, a pulmonologist, had said so plainly. She may be used to this information, but my family and I weren't comfortable with this. I leaned back from the window to look more directly at my reflection. God, becca, pull yourself together. I scolded myself as I wiped my eyes with the back of my hand. I had calmed myself down before I could cry when the news was told to me, but now my face was dripping wet, looking like we are moving closer to the transplant. Dr Conrad's voice echoed. I sniffed quietly. I don't want my parents to know just now how scared I really am.

Speaker 3:Fear, one of the scariest feelings in the world. There was no way around it. Once fear gets inside of you, it eats away at you. Fear becomes a part of you, moving closer to transplant. I shivered as the words came back to mind. I clenched my iPod, wishing the music could drown my fears. I searched through my library trying to find a happy song, hoping that would help. It didn't, I was too wrapped up with the idea of needing a transplant that I couldn't even hear the song.

Speaker 3:I pressed my small forehead up against the window again. I stared at my reflection, thinking I looked like an idiot, with my nose scrunched against the glass. An enormous sigh escaped my lips, making a light. Frost sat on the window. I broke away to look at the frost and I drew a heart in the middle with my finger. Then, mad at my heart, I wiped all the frost off with my sleeve. I pressed my hand to the window, feeling the coldness of the glass on my palm. I felt something small and wet roll down my face. I wiped my eyes with the back of my hand, but that didn't stop the salty tears from dripping onto my lips.

Speaker 3:I had kicked the back of my mum's seat, trying to get my anger out. You okay? My mom inquired, feeling the kick on the back of her chair. I started nodding my head but then quickly changed to shaking. I couldn't keep it in any longer. I let my head fall into my hands and I sobbed Boo, what's wrong? My mom asked, taking my hand in hers. She didn't need an explanation, though she already knew I don't want to die. I choked out, hence dying my hands. My mum gave my knee a gentle pat before speaking calmly I don't want you to die either, boo. I already knew that, but what I wanted her to do was promise me I wouldn't die, not now, not later, not ever. "'promise me, mum, promise me that I won't die'. I begged her, lifting my head from my hands to look her in the eyes. "'we are trying, boo. We're trying. I can't promise, but we are trying'. A note from Chris Atherton, Becca's mum.

Speaker 3:Becca had dreams. She loved life. She loved people. She was afraid she would be forgotten. Please hold her close when you graduate. Start a new job, hang out with family, try a new recipe, go to heart camp, share a low-salt option, get married. Welcome children. Stand up for those being excluded. Need strength. Ride a thrilling roller coaster. Give a speech. Remember with your siblings, volunteer your time. Grow old, listen to someone who is hurting. Please let Becca walk beside you to share in your joy. Please help her, through you, to continue to make a difference. Becca forever loved, forever missed, forever. 26. 9th of October 1992 to the 12th of October 2018.

Speaker 2:Free Falling by Margaret Raymond. I was playing in a sandbox, one not big enough to sit in but large enough that I could bury the therapist's toys in it. The wooden dolls with bendy arms and legs were a favorite, since similar ones were hogged by the popular kids at school. Sessions were often boring unless I initiated what we'd play. So that day I buried the doll with the yellow braids. What happened to her? Margaret the therapist asked she's dead. I can recall the silence that followed, because I experience it to this day, when my brain spits out a truth I'm not ready to unpack. Eventually I realized what I'd done and quickly dug the girl up, saying ta-da, she's alive, see, look. I held her out for my therapist's inspection and waited for her to agree. She must have reacted in some manner, but what I recall is her bowing her head and writing furiously in her notebook.

Speaker 2:My understanding of my life before the age of five comes from stories like these shared by members of my family. Recalling anything before the age of five is like attempting to overcome my fear of needles. It's nearly impossible. I rely on these stories to gauge who I was during a time I've blocked out my almost superhero-like power to forget scary things and the bright red scar from the tip of my sternum to the middle of my abdomen were not what made me feel different. It was my ability to protect myself from hard truths that, when finally forced to face them, made me realize exactly how I was different. I grew up too fast, faced death too early. I wanted to know the why of life while trying to stay young. It was a strange combination emotionally older because of the medical trauma, yet purposefully attempting to regress in academics. It was my way of trying to stay young. When the world forced me to grow up, I didn't have a near-death experience, so I can't say for sure why I was preoccupied with the meaning of life and what happens after you die, but I was. I am. We look for answers from the people who care for us, but when their answer to the what happens when we die question is well, do you remember what it was like before you were born? It makes you feel like you're free-falling.

Speaker 2:I'm in my late 20s and I often feel like I've jumped out of a plane with no parachute. I hate this feeling with a passion, but no one, not even the best therapists in the world, could have fully prepared me for every moment I'm to feel uncertain or uncomfortable. That's what I've learned. Anxiety is uncertainty and uncomfortableness. With this knowledge, I've at least been able to identify which one I'm feeling and take steps to calm myself down. For example, today I had an MRI with a contrast solution, consequently, needles. I've been anxious for the last four days. My anxiety has led to jitters, stomach upset and enhanced sense of smell. Yes, this one is strange, but it happens to me. So what do I do about it?

Speaker 2:I share my fear with the medical professional. So after I assured the magnetic resonance imaging MRI technician that, no, I wasn't going to pass out and that, yes, I would probably cry my eyes out, he said I wasn't going to pass out and that, yes, I would probably cry my eyes out. He said I could just give you some numbing cream. Excuse me, can you tell I'm slightly annoyed at having paid therapists to tell me none of this Numbing cream, apparently, is commonly given to patients who have a needle phobia. So while therapists were going off about costly exposure therapy options, there was always a prescription tube of numbing cream that I could not only request at medical procedures but that I could buy at the pharmacy. I say numb me up.

Speaker 2:Ten minutes later, the IV was in and I was crying, even though I felt nothing except his hand on my arm. It had triggered me. That's the strange thing about trauma it doesn't ever really go away. It's just like my heart will never have normal anatomy. I will always have tricuspid atresia, ta, even if I get a transplant. I'll consider myself a TA survivor because the condition doesn't make me who I am.

Speaker 2:My experiences do my ability to endure does. Enduring, however, is not necessarily living. For me, enduring is living moment to moment. That is a coping mechanism. I developed to handle the unscheduled visits of an Indian phlebotomist and the nurses with sympathetic smiles and freezing hands. That coping mechanism served me well, really well, except for when I was ready to stop fearing the future.

Speaker 2:I've learned that living in a moment means holding your anxiety for what's to come at arm's length. And as I get older and my health starts to change, I know my coping strategy needs to as well. I've sought therapists, attempted meditation and yoga, except it did nothing but force me into my old coping strategy staying in the moment. I needed the opposite, like exposure therapy to the future. What worked? Besides realizing the medical community had held out on me.

Speaker 2:I stumbled upon a therapist who had an answer no one else in her profession had thought to share. Of all places to meet her, a professional development day at work. She spoke about anxiety, how it is ruled by uncomfortableness and uncertainty. This was the missing link. I needed to recognize that life is passive without moments of uncomfortableness and uncertainty. What makes life active, or in my brain, worth living is overcoming those moments instead of pushing them away or trying to forget.

Speaker 2:Living moment to moment without preparing for the future was enabling my anxiety to control how I live. I'd been attempting to perpetually be comfortable and certain. Living doesn't guarantee either. Once that clicked, my anxiety lessened. Did it fix it? No, have I completely overcome my trauma? No, although it may lessen with time, I don't think I will ever be rid of it.

Speaker 2:I'm still the little girl trying to make sense of death, trying to uncover all the dolls in the sand. Trying is ultimately the difference between living a life passively or actively. I'll make mistakes, I'll resist change, I'll fall into old habits, hide myself in a comfortableness of certainty. This cycle may continue, except now I have the knowledge to recognize the pattern and the motivation to pick up the shovel and dig myself out. Margaret Ellis Raymond is a freelance developmental editor who believes everyone has a story and unique voice. She was born with trichospinatresia and shares her medical journey on YouTube under the channel name Unbeatable. Her hobbies include photography, saving the monarch, butterflies and a daily habit of laughing too much. She currently lives in a beautiful state of Maine.

Speaker 3:You Can't Even Imagine by Becca Atherton. You can't even imagine what it feels like to know you're dying. You can't even imagine what it feels like to look at your parents, knowing you may never see them again, or how it feels to look around a room bursting with loneliness and know that this place, this frightening place, may be the last thing you see before you die. You can't even imagine the horrifying embarrassment of having to ask your mum to help you to the bathroom At age 13,. Your strength is too fragile for you to even undo your own hospital gown. It feels as if you are back at age two, with your mum guiding you onto the freezing porcelain toilet, then back down. Your dignity is stolen away from you because of your own body. You can't even imagine looking at yourself in the bathroom mirror and seeing yourself for what might be the last time, the last time you see yourself, and all you can see is your sump and eyes of sickness, the paper-white complexion of a malicious infection eating its way through your body, slowly swimming through your fragile veins and into your bloodstream. You can't even imagine the sadness that consumes not only your mind but every inch of your trembling body when you see for the first time in weeks just how sick you truly are. You can't even imagine the terror of having your life placed into the hands of someone else. You can't even imagine the fear that overwhelms you when the mask is placed over your face. The plastic smell of medicine consumes your lungs and you plead please don't let me die. You know you are no longer in control of your life. You can't even imagine what it feels like to know you may never wake up from not only surgery, but also from this all too real nightmare.

Speaker 3:Baker Atherton was bright, beautiful, inclusive, kind, caring, brave, with a little bit of sass. She was a public speaker and an advocate for anti-bullying and congenital heart defect awareness. Becca has a blog where she shared her CHD journey. She was a Yelp elite food critic with an emphasis on low salt options. Becca was fluent in American Sign Language. She was a mentor and an inspiration to many. She made broken look beautiful and strong look invincible. She walked with the universe on her shoulders and made it look like a pair of wings. Ariana Dantzou Becker. Forever Loved, forever Missed. Forever 26, 9th of October 1992 to the 12th of October 2018.

Speaker 2:That concludes this episode of Heart to Heart with Anna. Thanks for listening today. I hope you found this program helpful. Please sign up to be a participant in our book study, especially if you're interested in taking part in Volume 4 of the Heart of a Heart Warrior series, as I'm hoping Deanna will. You can learn more at babyheartspresscom. I'll put a link in the show notes. I appreciate Deanna Altamira sharing her helpful book with us and I'm grateful to Megan Tones for helping me create this wonderful audio book so everybody can hear the inspiring stories we put together in the heart of a heart warrior. I'm also thankful for you, my loyal listeners, and remember my friends. You are not alone.

Speaker 4:Thank you again for joining us this week. We hope you have become inspired and empowered to become an advocate for the congenital heart community. Heart to Heart with Anna, with your host, anna Jaworski, can be heard at any time, wherever you get your podcasts. A new episode is released every Tuesday from noon Eastern time. You.