Heart to Heart with Anna

Revitalize your spirit and connect with the vibrant congenital heart defect (CHD) community through 'Heart to Heart with Anna,' the pioneering podcast that has been inspiring and informing listeners since 11-12-13. Join us as we dive deep into the personal journeys, triumphs, and challenges of Survivors, their loved ones, esteemed medical professionals, and other remarkable individuals within the CHD community.

With unwavering dedication, our heartfelt conversations bring to light the stories that need to be heard. Gain invaluable insights, expert advice, and a sense of empowerment as we explore the multifaceted world of CHD. Our mission is to uplift, educate, and enrich the lives of every member of this incredible community.

Embark on a transformative listening experience where compassion and understanding thrive. Discover the resilience and unwavering spirit that resides within each person touched by CHD. Together, let's build a community where support and knowledge flourish, bringing hope to the forefront.

Tune in to 'Heart to Heart with Anna' and embark on a remarkable journey that will leave you inspired, enlightened, and connected to the beating heart of the CHD community.

Heart to Heart with Anna

Threads of Resilience Sewn by Heart Moms and Their Children with CHDs

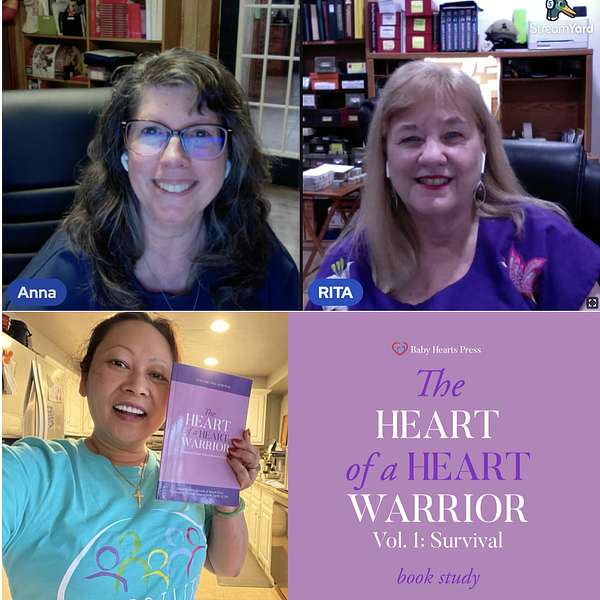

Navigating the torrent of emotions that come with being a heart mom to an adult child, Rita Scoggins and I, Anna Jaworski, unfold the layers of our unique journey. Our intimate conversation traverses the evolution of care, from the hands-on nurturing of our children's younger years to the complexities of supporting their maturity and independence. We delve into the potent mix of pride and concern, sharing stories that resonate with anyone who understands the pull of a parent's heartstrings as their children, like Rita's daughter Victoria, and Anna’s daughter Hope, carve out lives shaped by both their challenges and triumphs.

This episode continues with reading from The Heart of a Heart Warrior Volume One: Survival. In this episode, co-editors Megan Tones and Anna Jaworski, take turns reading essays from the book. In Chapter One we read the narratives of heart warriors who've faced body insecurities and the trials of scoliosis with courage. Laura Ryan's story, in particular, shines as a beacon of hope; her transformative experience at the waterslides in Lancaster, learning to embrace her surgery scars, offers a deep dive into the power of empathy and connection. We hear how individuals like Michael McKelvey and Dajah Scrivner channel their pain and resilience into poignant expressions of life with CHD.

Our episode doesn't simply share stories; it offers a lattice of support, exploring how adaptive clothing and familial love can buoy spirits amidst adversity. As we discuss the importance of finding strength in community and the solace of shared experiences, we invite you to join us in a space that celebrates overcoming obstacles and the beauty of human connection. For all who walk the path with heart-defect warriors, this conversation is a testament to the enduring spirit and the ties that bind us all.

Rita’s other podcast episodes:

Rita, Victoria, and Heidi Scoggins on The CHC Podcast: ‘Taking Control of Your Heart Condition’

Rita as a Guest Host on Heart to Heart with Anna interviewing Laura Ryan. ‘Heart Warrior Mom Raising Children to Adulthood’

Rita and Victoria Scoggins on Heart to Heart with Anna: ‘Congenital Heart Defect Awareness 2015’

Learn more about our The Heart of a Heart Warrior Volume One: Survival Book Study and join us to discuss the book and share your stories.

Anna's Buzzsprout Affiliate Link

Baby Blue Sound Collective

Social Media Pages:

Apple Podcasts

Facebook

Instagram

MeWe

Twitter

YouTube

Website

I want her to live her life, and I know you feel the same way. Our children have earned the right to live their lives the way they want to.

Speaker 1:But I do find myself getting stressed. Welcome to Heart to Heart with Anna. I am Anna Jorzi and your host. I'm also a heart mom to an adult who was born with a single ventricle heart and is 29 years old. That is the reason I am the host of this podcast. With me today is my dear friend, rita Skogins. Rita is also a heart mom. We met online about 27 years ago. Rita wrote for my book A Heart of a Mother and her daughter wrote for the Heart of a Heart Warrior.

Speaker 1:Victoria was born in 1983 with tricuspid atresia. She had the Pontian in 1989. Victoria lives in Arizona, where she works for the VA hospital as a hospital administrator, and Rita, like me, lives in Texas. Rita has been on Heart to Heart with Anna numerous times. Most recently, rita, victoria and Heidi, rita's granddaughter, came on our program after discovering her granddaughter had a heart condition and it wasn't diagnosed until she was a teenager. This surprised the entire family. Before that, rita and Victoria came on my program for Wear Purple for CHD Awareness Day, which occurs the second Friday of every February since 2014.

Speaker 2:Can you believe it's been 10 years, rita. I know I think it was probably the year before that, but we really didn't do much with it, yeah.

Speaker 1:I'll have the links to those two episodes in the show notes. After our interview, meagan Tones and I will take turns reading essays from chapter one of the Heart of a Heart Warrior. You can sign up to take part in a book study of volume one on our website, babyheartspresscom. We'll be discussing the book Mondays from 5.30 pm to 6.30 pm, usa Central Time. We'll discuss the book for the first three weeks, and the fourth week We'll have a Jeopardy game where people can win prizes. All the questions will be based on volume one and what we discussed in the book study sessions. Now on to our program. Welcome back to Heart to Heart with Anna Rita. Hi, anna, it's good to be here again. I always love having you on the show. I decided we need to have more episodes where we veteran heart parents are talking about what it's like to have an adult with a CHD, because I think it's really different to have an adult with a CHD versus a baby. What do?

Speaker 2:you think, oh, definitely, most definitely. We're no longer the one giving the day-to-day care like we were when we were children. So that's a big difference. And sometimes we don't know everything that's going on with them because they have to tell us we're not there, or some of us aren't anyway, some of a long ways away. So that's a big difference. Yeah, and of course we worry about them all the time. Yes, I agree.

Speaker 1:So today we're really just going to focus on what it's like to be the parent of an adult with a CHD. I know we've talked a little bit about this in the past, but what do you think is the biggest difference between parenting a baby and parenting an adult?

Speaker 2:Well, the baby takes a whole lot of time. It's constant care. There's a lot of doctor visits, a lot of going to the hospital, a lot of things that as an adult the adult CHD for the most part takes care of that stuff by themselves or for themselves.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I would agree with that too. Definitely, the quantity of time to care for them is different than when they're caring for themselves, because both of us are lucky enough that our children are independent and they don't live with us anymore.

Speaker 2:Right. Victoria hasn't really lived with us since she was 18 when she went off to college. She's been back for summer breaks. Now she's a working woman.

Speaker 1:I know it's hard to believe that she's as old as she is. I'm so proud of her that she's made it and is doing so well. She'll be 41 in March.

Speaker 2:Wow.

Speaker 1:Wow. So she has a birthday coming up in a month and she'll be 41.

Speaker 2:Yeah, she had a big birthday party for herself. The theme was I made it when she turned 40 because she said she didn't think she never might get to 40.

Speaker 1:Wow, that's amazing. Well, I'm so excited for her and I was so happy when she wrote for the heart of a heart warrior. I wasn't 100% sure I could twist her arm enough to actually make her do it, but she did, and I thought she did a really good job. And one of the things she talked about in her essay was how her pediatric cardiologist had told her as a teen that she would have to have good medical insurance and for her to take that into consideration when she was looking for a job. So how did you feel when Victoria chose a career in the medical field?

Speaker 2:She already knew she wanted to do something in the medical field. But she doesn't like needles so she didn't really want to do anything clinical. She had decided in undergrad that she wanted to go into the medical administration hospital type administration. When she was in grad school her professor had experience with the VA Veterans Administration and he guided her and encouraged her to seek that out as employment because he knew that she would always have good insurance to the government.

Speaker 1:Were you surprised she didn't choose to work for a children's hospital?

Speaker 2:Not really that's what she really wanted to do, but she's very practical too, and hospitals have a lot of politics they do, so you don't always know that your job is that secure, or with the government, your job is pretty secure.

Speaker 1:This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. The opinions expressed in the podcast are not those of Heart should unite the globe, but of the hosts and guests, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to congenital heart disease or bereavement.

Speaker 3:You are listening to Heart to Heart with Anna. If you have a question or comment that you would like to address on our show, please send an email to Anna Jaworski at Anna at hearttoheartwithannacom. That's Anna at hearttoheartwithannacom. Now back to Heart to Heart with Anna.

Speaker 1:Before the break, Rita, we were talking about some of the concerns that we have as parents of an adult with a CHD, but both of us are in a unique position since our daughters are single. How do you feel about Victoria living so far away from you?

Speaker 2:alone. I've gotten used to it. I guess she left our hometown when she was 18 to go off to school in Austin, which is a good 350 miles from our house. She went to grad school in Houston, which again is about 350 miles from here. Her first job after graduating was in Montgomery, Alabama. She went there for about two years and then she ended up back in our hometown for about four years with her second job with the VA, and then she was ready for a move, mainly because there's no medical care for her here in the valley. So we encouraged her to move somewhere where she would be in a city with access to the care she needed. And it was a little further than we thought she would go, but we've gotten used to it. It's a beautiful city, Beautiful city.

Speaker 1:I guess what I was referring to with this question was more about the fact that she doesn't have a partner, that she doesn't have a roommate, even somebody living in the house with her. Does it concern you that she's all by herself, or are you the kind of mom like my mother and I were that talk on the phone every day to each other?

Speaker 2:I call her every day, but she doesn't call me every day. She's so.

Speaker 1:That was with me, and my mom too. She called me every single day.

Speaker 2:When my mom was alive, either she called me or I called her every day. We touch base every day. But Victoria's not really like that and she's busy, she works hard and then by the time she gets home she's tired and she has her own social life. But yes, I do worry about her being there alone. She's had to call the ambulance once at this place where she's living now, because she was having a little rhythm here and had to be shocked back into rhythm. That's happened a couple of times since she's been in Phoenix. So yeah, that's a little nerve-wracking when you're so far away.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I think it's nerve-wracking, even when you're in the same city. My heartwarrior lives in the same city as I do, and it's not a big city, it's a small city. However, I don't talk to her every day. She is super busy, she has a lot of friends and a lot of social activities, so I don't call her every single day and I worry sometimes what if something happened? What if she passed out and nobody noticed? Because I don't talk to her every day?

Speaker 1:Whenever I think about that, I find myself calling her more regularly. I'll call her several days in a row and then I think, well, she doesn't always answer. Just because I'm calling Doesn't mean she answers. She works as a pharmacy tech and she's not allowed to have her phone on when she's at work, and I never know her schedule because it's different every single week and she doesn't send me her schedule every week, so I don't know what it is.

Speaker 1:So then, if I don't hear from her, I don't know if it's because she's at work or if it's because something is wrong with her, and then that makes me stress out even more. So I think that's one of the stressors though, don't you? Oh, yes, definitely. I have a heart healthy son and when I reach out to him and he does it call me, I know Ashley's there and Rowan is there and he has plenty of people who are checking up on him every day and that he's probably fine. He's just too busy to talk to me. But I find myself worrying differently for hope than I do for Joey.

Speaker 2:When I call Victoria, she usually will answer right away, and if she doesn't, she'll call me back soon. Now, if she doesn't call me back within a couple of hours, then I get a little stressed. I guess you call her With anxious.

Speaker 1:Yeah, I mean, I think it's normal for mothers like us to stress because, even though I live in the same town, I don't know if I could get to her in time, if she really needed me, right, because we know that things can change in a heartbeat. Exactly, yep, and I think that's one of the things that's different, being the parent of an adult versus a parent of a baby. Your baby is with you, or at least for us, I know, for having talked to you before. We took care of our babies all the time. They were in our arms or in the next room at the furthest, so we had our eyes on them all the time.

Speaker 2:I think, for me. I hate for Victoria to think that I'm always worried about her, that she's my source of worry, and she doesn't have children, so I don't think she realizes either what that's like.

Speaker 1:Yeah, you carry a baby for nine months in your body and they become part of you.

Speaker 1:And they've even done studies lately in the brain to show that mothers have certain connections neurologically with their children that the fathers do not have. Right, and I agree with you. I don't want hope to listen to this episode and say, oh my gosh, mom's always worried about me. I better do things differently. I want her to live her life, and I know you feel the same way. Our children have earned the right to live their lives the way they want to. But I do find myself getting stressed.

Speaker 2:Well, it's nice to hear somebody else say that, because sometimes I think it's just me. I'm just can be on pins and needles. Sometimes you know what's going on. Why hasn't she called?

Speaker 1:And I think that's one of the reasons why it's important for us to do a podcast episode like this to let parents know they're not alone and this isn't something that you necessarily talk about with your friends, because their adults are independent. They're doing great, and I don't really think about these questions that I'm asking you now, but I'm so glad to know I'm not the only one that worries about that. Even now you wouldn't think you have to worry, but I do. No you do.

Speaker 2:It's my job.

Speaker 1:The job's not over. No, it's never over. It's never over. So for those of you who think, oh, all we have to do is get our kids to 18. Guess what it's not over? What's our 18?

Speaker 2:And I think sometimes our heart warriors maybe don't want to think about that in the blink of an eye or a beat of the heart that something could happen.

Speaker 1:Well, none of us do. We are more attuned to the fact that things can change and we have seen it. And now that we're older, many of us have been in a car accident. Or we know of somebody who had a heart attack, who was heart healthy but had a heart attack.

Speaker 2:We've lost so many of our heart warriors that we know what it means to have a CHD.

Speaker 1:And you and I are so connected in the CHD community. Not all heart parents do what we do. They're not on Facebook, they're not talking to all of these people, so maybe they don't know to the same degree that we do. But we've seen our friends and our friends' children have arrhythmias, have strokes, have all different kinds of things. So in some ways I feel, like Rita, we know too much Sometimes, yeah, and yet I feel that knowledge is power, exactly, and that we do a good job of keeping ourselves aware of excellent opportunities that may present themselves for our kids. So, in the event, something does happen, we can say, hey, I just read about a study at CHOP or I just read about a study at Neoclinic, right, something like that. And I think that's one of the reasons why I still find it so important to do the podcast and to keep up with everything that's going on, because it could benefit Victoria, it could benefit Hope or some of our other friends, right? Yeah, you feel the same way, yep.

Speaker 2:Thank you.

Speaker 1:Okay, one of the things that parents of our generation have been accused of is being helicopter parents. I think it's especially difficult for us, as parents of a child with a CHD, not to have her and not to feel more concerned for our daughters than for our heart-healthy sons. Do you think you were a helicopter parent with Victoria when she was young?

Speaker 2:I don't think I was a helicopter parent as much as some of the parents are today. It's quite obvious that she's very independent. So if I was a helicopter parent, it didn't stop her from doing what she wanted to do. I helicoptered her, maybe more, if that's a word, than the boys, than the other two, but she was the only girl and she was a baby and she had a complex heart defect. I felt like I was doing my job. That was what I was supposed to do.

Speaker 1:That's how I felt too. I think for us, especially in the age that we were raising our kids you were raising Victoria mostly in the 80s, I was raising hope in the 90s, and way back then we didn't know as much. There were no manuals to help us, Even in the intercare between surgeries. They could send us home with any information except, hey, when the kids blew enough, then they're going to need their next surgery. I mean, everything was extremely uncertain. I felt like they were really learning on our kids.

Speaker 2:Well, and Victoria is a good what? 10, 12 years older than the world? Yeah, over 10 years.

Speaker 2:Yeah, hope will be 30 this year, yeah so about 11 years, at least at 10 years the internet came about, because Victoria was about 10, 12 maybe when the internet actually started that we had access and I found some heart parents. That was the first time I really talked to other parents. So, yeah, we came home with our babies with no manual, no help really. I was lucky that we had a very good pediatrician that kept a very good eye on her and we also had a very good pediatric cardiologist in Brownsville, which is about 25 miles down the road, and he kept a very good eye on her. So those things helped. Like Victoria.

Speaker 1:We went from the first surgery to what now would be considered the third surgery without having a second surgery. And then Hope has had a frontier revision. Has Victoria had a frontier?

Speaker 2:revision.

Speaker 1:Yeah, she has not.

Speaker 2:That's amazing. Next step is probably transplant. She gets to that point Right now. She seems to be doing well.

Speaker 1:Yeah, she does seem to be doing well. I love it when she posts photos. She doesn't post photos that much, so that makes it really stand out to me when she posts a photo, but okay. So the last question I'm going to ask is do you ever worry that you might offer to help Victoria too much? Do you find it difficult to know when you're being a good parent and when maybe you're doing too much? Not really, because I feel like we walk a fine line right, and I'm talking about between my heart healthy kid and my kid with a CHD. It doesn't matter. What do you mean by helping them? For example, I remember when you flew to Arizona to help her pack up her house and move to her new house. Some people, especially people who don't have children, may feel like, oh, she could have packed herself up. Why did you have to be the one to do that? Well, she's not married, right? If it's the first time you have no problem with that I would do the same thing Exactly Right.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:Maybe Eva, financially. I know that I have helped my kids at various times financially and I know that some people may feel like they're adults and let them grow up, let them pay for their own this or that, but I have felt that I know I'm not immortal. Someday I am going to die. I have two choices Either I can give my kids money now, when I see that there's a real need and I can be there to witness that being helpful to them, or I can say no, take care of it yourself. After a grown up, you have to learn how to do this. And then, when I die, they get more money.

Speaker 1:So Frank and I have talked about this and we have decided that, yes, of course we're putting aside some money to help them when we die, so that they will have a little something extra and they don't have to worry about paying to bury us or anything we already have that taken care of, but I want to be here to help them. But some people might say, anna, you're not letting them grow up, you're not letting them suffer hardship, and that is where you find what you're made of.

Speaker 2:I mean, we've helped our kids along the way. Of course it's just part of being a parent. I don't think we've helped them too much. They all have jobs. They're all productive citizens of our country. We give them what we can when we can, if they need it, if we're able. I don't consider that helping them too much.

Speaker 1:Rita and I will continue the conversation next week. I'm happy to share with you that after Megan Tones heard me reading the beginning of the book last week, she has agreed to take turns reading the essays with me. This is awesome because you'll have a chance to hear Megan Tones with her beautiful Australian accent and you'll also hear me with my American accent reading the book. Megan and I were co-editors for the book the Heart of a Heart Warrior and I sincerely hope you enjoy listening to Chapter 1.

Speaker 4:Growing Up with Congenital Heart Defects. When Anna first put out the call for essays on heart warriors' experiences and overcoming obstacles, I was eager to get started on my essay. My head was so full of ideas from things that had happened to me as a child or an adult. Do I write about my flashes of memory as a five-year-old in hospital, think fed pieces of lemonade, ice block as I emerge from surgery, or stalking around the shiny disinfected jungle dressed in a leopard costume? My mother made me In my imaginary play. I was always strong and powerful, a stark contrast to how I felt in life. Or do I write about the open-heart surgery I had when I was 10 that I still don't really understand, about the growing sense of unease as the atrial flutters got worse, my nervous friends or the nurse who read me Paul Jennings' books on the day of my surgery? One change between five and ten years of age was a growing sense of how I differed from others. From the stories and poems you will read in this chapter, you will see that difference runs through all of them, whether it is being self-conscious about a new scar as a teen, as in Laura Ryan's it Takes a Child or facing stares and questions about a personal and traumatic health battle Ms Darja Scrivner describes in her poem aptly titled I Am Different. Tyler Sajak and I write about other complications associated with CHD vocal cord paralysis and scoliosis respectively and how they affected us socially.

Speaker 4:Fortunately, from my time at school I cannot recall any bullying incidents related to my heart. My fellow students were very kind in that respect. When I was in hospital at ten there was another boy on my ward. I think his name might have been Gavin, but I know for a fact his cat's names were Ben and Rambo. I always had a better memory for animal names than people. He told me a story one day. I was in the playground one time and this other kid started making fun of me because of my pacemaker. So I kicked him in the nuts and he fell off the jungle gym. When I look back at my time growing up, I see how fortunate I was that my classmates were so kind to me, even as a teenager, when I wore a back brace for my scoliosis. I can count the number of nasty comments I received on one hand. Unfortunately, jenny Booster did not have the same experience, as she detailed the horrific bullying she endured for her heart condition in a soul unbroken. However, throughout these stories there is a sense of acceptance, resilience and growth. This is especially clear in Michael McKelvie's poem. Our authors in this chapter range from their early 20s to their early 50s, yet there are common threads through them. I hope you enjoy the essays and poems about growing up with congenital heart defects. It Takes a Child by Laura Ryan.

Speaker 4:In May 1986, I had my second heart surgery. I was 16 years old and had a fresh zipper scar. Mum, can't we go somewhere else for our vacation this year? I asked my mother as she was packing her suitcase. Laura, you love Lancaster, she exclaimed. But, mum, we always go to the waterslides in Lancaster. It's time we did something different. I said I don't know what's gotten into you. My mother said this has always been your favourite place on earth. I did not want anyone to see my scar Swimming without a shirt covering my bathing suit and my scar was out of the question. Why didn't my mother understand that? It was the first time in my life I was self-conscious about my body. I never had a zipper before my first heart surgery was done when I was six weeks old. It was a closed heart surgery done through my side by the age of 16, the scar was old and faded. Now I had a zipper scar running down the centre of my chest. It was fresh, only three months old and still red and bumpy.

Speaker 4:As we approached the slides, the smell of chlorine was in the air, people were applying sunscreen and a comfortable feeling of summer wafted over me, only to be quickly replaced by dread. There were new owners, new owners with new rules. No shirts allowed on the slides was printed in large red letters, and I felt my heart sink. Let's go, said my younger sister. I refused to go. I wanted to go, but there was no way I was gonna take my shirt off.

Speaker 4:I watched Michelle dash to the slides, squealing with delight. I burst into tears. Why are you crying? Dad exclaimed you love it here. I turned away. What's wrong with her? Dad asked mom, why didn't they understand? Couldn't they see this ugly red scar on my chest? Didn't they understand? I didn't want people staring at me. Laura, you're being ridiculous, dad said. He threw up his hands, shaking his head, and walked away from me. Mom quietly said Laura, you are strong. Your scar is proof of how tough you are. You just don't understand. I sobbed and hid my face in my hands. Suddenly I heard a shout Look, mom, look. Said a very excited little boy.

Speaker 4:As another family entered the picnic area, two little boys about five and seven years old were dragging their mom to a table near us. The older of the two started stripping off his clothes. Come on, mom. He shouted. It's getting crowded, let's go. The younger boy slowly walked over to the picnic bench and sat down. He started crying. Come on. The older boy cajoled. He tried to help his younger brother take off his shirt, but the little boy pulled away from him. Mom started talking to the little boy's mom. My son just had heart surgery. The other mom whispered. Mom nodded and said I understand. What kind of heart defect does he have? The two mothers started talking a mile a minute.

Speaker 4:By this time I had stopped crying and was staring at the little boy. He's too young to be self-conscious about his scar. I thought, yes, my daughter has also had open heart surgery. Mom was telling the other mother. The boys stopped crying and stared at me. I made a funny face at him. I crossed my eyes. Yes, it was the longest day of my life, said one mother. I stuck my tongue out to the side and crossed my eyes again. The boy copied me. We are being silly. I thought we can both have a lot of fun.

Speaker 4:And he was born without an ear lobe. The boy's mom continued. He's had all kinds of reconstructive surgeries on his ear and they still aren't finished. I started thinking about it. I wore glasses and they did not bother me. I had a scar on my side and that didn't bother me.

Speaker 4:It was then that something changed in me. I walked over to the boy and said hi, I'm Laura. Would you like some chips? We bit into the salty potato chips and gobbled them down while our mothers bought us each a Coke. We talked, sipped our cold drinks and laughed at some of the other kids' silly antics near the slide. After a few minutes I took off my shirt. The boy smiled and took off his shirt. Looking good, I said and gave him a thumbs up sign. When he smiled back at me, it lit up his eyes. Simultaneously we said let's go. As we grabbed the waterslide mats and started walking hand in hand to the kitty slide. Just a minute the boy's mother exclaimed Laura, you're burned to a crisp. Mum admonished as she tossed me a tube of sunscreen.

Speaker 4:We spent the rest of the afternoon going up and down the Jack and Jill kitty slide, we got water up our noses and had to go back to get more sunscreen before the day was done. Chlorine burned our eyes, but we didn't care. Thanks to a young boy, I started enjoying myself and got over being self-conscious about my zipper. All I had to do was look beyond myself to see the situation more clearly. Sometimes it takes a child. Laura Ryan was born April 9, 1970 in Brooklyn, new York, and raised in Queens, new York. She was born a blue baby with a single left ventricle and congenitally corrected transposition of the great vessels. Laura has two biological sons and has been married since 1995. She loves all animals and has cats, dogs, turtles and frogs. A little known fact Laura collects salt and pepper shakers.

Speaker 1:A Soul Unbroken by Jenny Booster. As the door closed, I walked to the corner of the bathroom and slumped into a fetal position With my arms wrapped around my knees. I bowed my head, closed my eyes and felt the tears slide down my cheeks. God, I whispered. Please take my life. I don't want to live anymore. I had just bewashe my hands in the bathroom when I heard the school's fire alarm bell ringing. Some girls started taunting me, saying why don't you just stay here and let the building burn and fall on you? Jenny, you're going to die young anyway. It was 1991, but those voices still haunt me to this day.

Speaker 1:The beginning of each school year, starting in preschool, my mother was invited to present a fun and educational lesson about the differences between my heart and a normal heart. Mom unrolled two big posters, one with a normal heart, any other with a hypoplastic left heart syndrome heart. Passing out stethoscopes to my peers, mom said here let's listen to each other's hearts. While my classmates took turns listening to each other's hearts, mom continued Jenny has a special heart. Others had to do surgery and she has a special machine in her tummy that helps her heart beat better, as if on cue. I would then lift my shirt showing my scar. Mom would then hold up an x-ray showing my chest and my pacemaker in my stomach. Sometimes Jenny gets tired, but she could still run and play with you.

Speaker 1:While most of the kids learned from mom's presentation, some classmates were unkind. In 1989, in preschool, sometime after mom's presentation, a little boy punched me in the stomach because he thought it would be cool to see my inside spill out. The next year I was walking outside before lunch and a little boy ran up to me. I stopped walking to look at him. I'm going to bring a gun to school tomorrow, he said Stunned. I started crying If you tell your family, I'll go to your house and shoot them too. For two decades I had recurring nightmares where this same kid, as a grown-up, would come to our house and kill my family members. As I hid behind the couch when the shooting was over, I would see them lying dead on the floor with a bullet through their heads. A common occurrence happened when I walked around the schoolyard during physical education, as I was unable to run laps for very long. My schoolmates then would run up behind me to shove me to the ground. While laughing at me and running off, they yelled you can't be our friend, jenny, since you can't run as fast as we can.

Speaker 1:Even in my lowest places, I knew God was with me throughout it all. My scar was nothing to be ashamed of, but rather something of beauty. It was God that knitted my heart. Psalms 139, 133, 14. Exactly as he wanted it, and he never makes mistakes.

Speaker 1:My bullying experiences continue to make me a compassionate counselor for others living with CHD. At six years old, all I wanted was to stop living. Little did I know that three years later I would be at a heart camp on an island, surrounded by kids who were just like me. They had scars on their chest, medicines to take and the understanding of what it's like to think that every day could be their last. If God took me home when I was six years old, I never would have known what it was like to grow up with people who understood what it's like to live every day with a heart effect, like the people I met at Camp de Corazon.

Speaker 1:I wish I could say that being bullied is all in the past, but I am now a woman in my mid-thirties. I feel I am expected to have a college degree, a successful career or raise a family. However, because of the limitations of my condition, I have had to determine what my life goals are. Some people have been very critical regarding what they think I should do with my life without considering the limitations of my heart effect. This has taught me that seeking the approval of others is like chasing after the wind Ecclesiastes 2.11. It is futile. If God had taken me home when I asked Him to, I never would have met Nick Busta.

Speaker 1:Nick came along when I least expected it. I caught his attention with a Bible verse, philippians 4.13. I can do all things through him. Who gives me strength? We were 14 years old when we met online in random AOL chatroom number 25. My profile said I was born with half a heart, hlhs. Nick said oh, that's really sweet. You're waiting for your other half.

Speaker 1:Nick soon learned the truth about my heart effect. Nick and I were practically inseparable, even though we lived 300 miles apart. For the first four years of our relationship we talked nightly for hours on the phone with calling cards. We emailed love letters to each other. Then it was finally time to meet in person. Mom, I fell in love with a boy online and I want to meet him. Will you please take me to meet him.

Speaker 1:God gave me Nick to help mend my emotional scars from being bullied. Nick believes I am beautiful, regardless of what my classmates used to say. My husband, nick, is my rock support and cheerleader who keeps me thriving. On July 14th 2007, I married my other half and best friend. God has not only blessed me with the most amazing husband I could ever hope or ask for, he has also blessed me with an incredibly loving and Christian family. They have all been there to encourage and strengthen me in my faith.

Speaker 1:Whenever the memories of my being bullied are brought to mind, I am reminded of my favorite Bible passage, james, chapter 1, verses 2 through 4, which reads Consider it all. Joy, my brethren, when you encounter various trials, knowing that the testing of your faith produces endurance, and let endurance have its perfect result so that you may be perfect and complete. Lacking in nothing New, american Standard Bible 1995. This is God's promise to me that, no matter what I was going through, he used my pain to help me grow in endurance and strength. I know that, whatever trial I face, I am assured that God has his purpose for me in mind. He has shown me that his plan and purpose was much bigger than that which I was able to comprehend at six years of age. I hope that one day, when I finally meet my Creator, I will be completely healed of my emotional scars and that God will make my heart whole.

Speaker 1:Jenny Boussa was born on June 25, 1985 at UCLA Medical Center with Hypoplasic Left Heart Syndrome, hlhs, or an underdeveloped left side of her heart. In essence, she was born with only half of a working heart. She grew up in Camarilla, california, with her close knit family. She became involved in the CHD community at a young age and attended Camp De Corazon, a camp for children with congenital heart disease, for nine years. In the summer of 2007, she married her sweet husband, nick, and is now a happy housewife who still advocates in the CHD community. Her advocacy revolves around her faith in Jesus Christ and sharing her story to give hope to others.

Speaker 4:Picasso by Megan Tones. My face grew warmer with each passing second as I stood touching my toes in the nurse's office, feeling the eyes of the nurse, my teacher and my classmate burning into my back, blood rushing to my face. I watched the nurse's feet pace back and forth behind me. Even when I closed my eyes I could hear the clop-clop of her high heeled shoes. This is taking too long. Something's wrong. I didn't find out how wrong until a few weeks later. In the specialist's office, he sat opposite my mother and me, the light reflecting off his spectacles making him look like a mad scientist in a horror movie. How could I have scoliosis and not know? With all the chest X-rays I've had, defects of the heart and spine often go together, he said bluntly. He turned on a light to view the X-ray. On the screen I saw a slight bend in the thoracic spine, a cross marked above it with a number thirteen still lucky thirteen. Over the next three years that number grew to twenty-three, to thirty-one. The crosses on my X-rays seem to get bigger too, reminding me that my body had gotten something else wrong. Megan, do you know any other girls at school with a brace? The specialist looked at me with his shiny, shiny eyes. What kind of question is that? I paused as my mind did the gymnastics to find an answer that would avoid me getting a brace. He was trying to break the news to me gently like that old not-so-fast joke All the sergeants who have a mother step forward, not-so-fast, sergeant Jones. We drove home from the apartment in silence, with me hypnotised by the white dotted line in the centre of the road an endless straight vertebrae. By the next week we're in another waiting room. I studied the goldfish glittering under the harsh tank lighting, listening to the endless bubbling of the filter. I was almost in my own world. When someone kicked my shoe, megan, I nodded Come on, let's go. Another doctor trying to be my pal Great.

Speaker 4:Within a short time I was wearing a tight body stocking, strapped to a rack which was like a hospital bed, but with soft plastic slats instead of a mattress. I stretched my body to lengthen and straighten my spine. We're going to make a body cast for your brace. He began wrapping a wet plaster bandage around my chest. I winced, expecting the bandage to be cold and slimy like seaweed in the ocean. It was warm and I breathed out as far as I could, filling the brace push against me. Was this what the next three years would be like? After what felt like an hour, the cast was dry and the doctor cut it off. What a relief, I thought, as I washed the plaster off my body and got changed again.

Speaker 4:A couple of weeks later, my brace was ready. It was made from hard, inflexible white plastic with dense foam on the inside and reminded me of the Stormtrooper armour from Star Wars. The doctor opened the brace from the back and wrapped it around me. I stood up loosely while you get used to it. He adjusted the velcro straps and the brace closed like a set of jaws jerking me right and left. I tried to breathe deeply and felt an itch on my belly, now out of reach. I looked at my reflection in the consult room. Aside from my heart condition, I had received the full horsemen of adolescent humiliation Bracers, headgear, acne and now the mother of all of them, a back brace.

Speaker 4:I tried to pull my jeans over my instantly wider hips. The waistband yielded, but there was no hope for the zipper. Next was a camisole. It revealed my brace in all its glory, especially on the left side, where the brace dug into my left armpit, with only track pants and t-shirts fitting me. I saw a silver lining. How about we go shopping, my mother asked.

Speaker 4:The teen girl section at the local department store was filled with medriff tops and tiny shorts, like an army of invisible mean girls. Thanks a lot, spice Girls. None of these will work. These clothes aren't really your kind of thing anyway. Mum said she was right. But the problem was I couldn't wear them. In the ladies section I had more luck. I don't want to wear stretch jeans. Fat old people wear those. Nobody will know. Mum said Just try them and see what you think. I was surprised in the change room. The jeans went over my brace and the zipper closed easily. They looked just like my old jeans. Those looked good, mum said, with a t-shirt. You wouldn't even know you were wearing a brace. Those jeans and a t-shirt became my uniform for that winter.

Speaker 4:But come summer there was another problem. All the dresses that hide my brace are from the old ladies section. I said they look like church clothes. I have an idea. Mum said my mother had sewed since she was a little girl and made clothes for me when I was younger.

Speaker 4:At first I thought I was too old to wear homemade clothes, but my only other option was looking like a 15-year-old granny. Look, she showed me some patterns of fitted dresses. I could make this in a fabric you like and adjust it so your brace doesn't stick out. I don't know. I hadn't been to a fabric store since I was little. I thought back to when the rolls of fabric were taller than me and I would run around the store like I was in a technicolor forest with the scent of wool and fresh cotton, looking for buttons with cute animals on them. Now I was on a mission. We left with a pretty blue floral cotton. I tried on the dress when it was finished, and what a transformation. For the first time since I started wearing my brace, I felt better about myself instead of worse. The brace faded away under the fabric, leaving only curves that were meant to be there.

Speaker 4:As a child, I sewed toys that quickly became frustrated with sewing clothes in home economics classes at school. Newly motivated by how good a well-fitting dress could make me feel and my disdain for department store clothing, I started sewing my own clothes by the time I was 16. I made a long purple maxi dress I wore until it was full of holes. When I was 17, my specialist gave me some good news You've stopped growing. You can discard your brace now. I threw my brace in a metal bin in the backyard. Then the bin mysteriously caught fire. Looking back, I wished I had kept the brace and turned it into some kind of art project, but the melt of mess expressed my feelings.

Speaker 4:Unfortunately, the end of brace-wearing did not mean the end of scoliosis. My spine still curves and rotates to the right, and on a bad day it feels like a flame licking up and down the length of my back, burning my nerves in its wake. One shoulder rotates forward, my ribs bow out front and back on opposite sides, and I have to go to a shroth therapist to manage the pain. My mother took me to a professional dressmaker about three years ago. I was shocked by how different the measurements of the left and right side of my body are. To help with the fitting, my dressmaker drafted separate left and right pattern pieces for my body. When I cut out a pattern, it looks like it's designed to fit one of Picasso's figures, but somehow it all comes together. When I put one of my dresses on, I still have that amazing feeling of being transformed by a piece of clothing that was made to fit me.

Speaker 4:Megan Tones was born in Brisbane, australia, in 1983. She was suspected of having a heart problem at six days of age when her mother noticed her gaining weight despite difficulty feeding. At four months of age she had a pulmonary artery banding and received an official diagnosis of ventricular septal defect VSD at two years of age. More surgeries followed, including a VSD repair at age five, a right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction at age ten and a mitral valve repair as an adult. Today she lives with her husband, matthew, four dogs, heart failure and the occasional arrhythmia. She works as a researcher at Queensland University of Technology and likes to travel, attend movies and the theatre not operating, and so paint and write. You can reach her at MeganJTones at gmailcom.

Speaker 1:Michael's poem by Michael McKelvie. Hearts woven, hearts been broken. Deep down my chest I've been sliced wide open, born not knowing scars clearly showing the pain and discomfort. But I am slowly growing the power of a man to understand what's in his hand. He's dumb, founded in the light, but still sticks to the plan. Unfolded, the truth untold to be shown. Scars lie even deeper than what he's ever known.

Speaker 1:Wicked limits hassled and strangled the life from within, fighting every breath for forgiveness of sin, Painted melodies of gluttony and sorrow. He often feels like his life is being borrowed. He fights and fights, just wanting to be heard. His heart sings, but without any words. His heart aches for just one day to be healthy. But even he knows money can't save him, no matter how wealthy. That's why he remains smiling and as happy as can be, even though his scars will never leave. Editor's note this poem was initially published on the Mended Little Hearts website. We thank them for permission to reprint it here. Michael McKelvie was born on January 15, 1992 in Sharon, pennsylvania, with double Outlet Right Ventricle, dorv, ventricular septal defect, vsd and total anomalous pulmonary venous return TAPVR. He has had four open heart surgeries. He loves basketball and is a huge Kobe Bryant fan Michael believes that if we are kind to one another, we can help change the world.

Speaker 4:I am different. By Darja Skruvner. I was only two years old on December 13, 2004. Sirens blasted as I laid on the floor. Paramedics bring me back following a cardiac arrest To be forever marked as different. Looking at my scar in the mirror, I knew I was different. People staring at me and asking what happened. I just stare at them and start to cry because I am different. Asking my gym teacher can I sit out? I might pass out, or just taking medication every day from a young age, going to doctor appointments just to see if everything is okay. Because I am different. Every year on December 13th I cry and people don't know why. Not every kid can tell what happened to them on a specific day. Sometimes I wonder why I am different. Darja Skruvner was born on July 6, 2002, with double outlet, right ventricle DORV. Her hometown is Clarksville, tennessee. Darja loves to work out and she has an eight year old Rottweiler named Ruby after her birthstone.

Speaker 1:Voiceless by Tyler Sejek. Growing up without a voice is an incredibly difficult thing to do. It forces you to figure out ways to cope with other people that most others never have to think about. From constantly being asked to repeat yourself to only speaking up when you think it's necessary. It gives you the incredible opportunity to become a superb listener. That was my life, for my first 14 years on earth.

Speaker 1:Although I was always involved in playing sports as a kid, the shortness of breath and lack of verbal communication made things tough, especially as I grew in. The fields that I played on got larger. This became especially pronounced when I started playing high school baseball the summer after eighth grade In Little League and Rec Leagues. I grew up playing shortstop or pitcher in most baseball games I played, but when I got to the first practice for freshman baseball team, I quickly realized there were much better athletes that also played shortstop and pitched. I also realized that we didn't have anyone who wanted to play catcher. My path of least resistance to playing every game was to sit behind a plate. I have always loved the strategy of baseball, and playing catcher is just like a second coach on the field calling pitches, giving signals to the rest of the team and calling out where the throw should go, since I'm the one who has the best view of the whole field. Despite having never played catcher before in my life, I quickly fell in love with the position. During one of our practices, my coach was hitting ground balls and fly balls to the rest of the fielders and I was attempting to call out where the throws had to go and if they should be cut off by the infielders. I was trying my hardest to get my voice out to them, but the fielders were struggling to hear what I was saying. My coach noticed this and I made the comment that my voice will be better to handle shouting instructions to the fielders next season, but until then this is what I'm working with. The coach asked how I knew it would be better next season, and to explain this we have to go back in time.

Speaker 1:The previous fall my father, brothers, our foreign exchange student and I were out in our yard playing football. The ball ended up on the ground and we all went to pick it up. We ended up in a pile on the ground. We all thought we were unharmed after this event, but a few days later my dad's voice went hoarse. As he was talking to my mom, he ended up making an appointment to see an ear, nose and throat doctor in Des Moines, iowa, the closest specialist to us. My dad got to talking with the team there and brought me and my history up.

Speaker 1:My parents were told that I could have the nerves that attaches to my vocal cords fixed, but it would require a rather invasive surgery and it would leave me with a large scar across my throat. But as he was talking about me and my voice, the doctor told my dad he could fix it. My dad asked how he would do it. The doctor replied that it would be a laparoscopic procedure. The doctor would go in through my left armpit area with three small rods one with a camera and two with the tools, and take a nerve from my throat that was used for swallowing and attach it to my vocal cord, inject some collagen into my vocal cord, since it was weak because I hadn't been moved in 13 years and I would have a voice. When I woke up from surgery we were all confused why we hadn't heard about this procedure before, since this is a common issue among congealed or heart-defect patients. The doctor told us he had just started doing it this way.

Speaker 1:The August between 8th grade and freshman year, after baseball season was over, I had the procedure done, I woke up and everyone was able to hear me. For the first time in my life. My parents were in tears when they heard. I called my maternal grandparents on our way home from the hospital and they were in tears as we talked. A few weeks before I had my surgery, my paternal grandfather had a stroke. He wasn't able to communicate very well because he lost most of his motor function after the stroke. When we got back home after my surgery, my uncle went to the hospital to visit my grandpa and he called me up, knowing that I had my surgery and that one of my grandpa's biggest frustrations was his difficulty hearing me. My uncle put me on speakerphone and brought the phone close to my grandpa and I just talked to him. For the first time in my life, my grandpa could hear me without all the barriers that we had previously. Tears streamed down his face. That was the last conversation that I had with my grandpa, as he would pass away about a week later. I don't remember what I said in that conversation, but I will never forget that feeling that I had and all the barriers falling just like that. When I walked into school a few weeks later, all my friends at school were happy to hear me and my baseball coach, who was also the history teacher, told me he was looking forward to hearing my thoughts in class and being able to call out instructions to my teammates on the diamond next season.

Speaker 1:Even almost 15 years later, I still struggled with some effects of not having a voice for the first 14 years of my life. Sometimes I talk too fast. I still listen before I speak. Most of the time. I don't always enunciate clearly enough for people, but gaining a voice has opened up doors I never thought would open. I was able to be on the radio during high school. I participated in healthy and unhealthy debates in school. I was able to give speeches in class without worrying if the teacher sitting in the back of the room would be able to hear me. Despite all the drawbacks that I had growing up, I don't know what I would do now if I didn't have a great family, friends and the ability to speak for myself.

Speaker 1:Tyler Sejak is a 29-year-old with hypoplastic lift heart syndrome. He holds a bachelor's degree in political science and currently works for the University of Pittsburgh. Tyler enjoys watching and playing sports, often going to Pittsburgh Pirates games and playing in local slow-pitch softball leagues. He can also be found watching movies and television shows in his spare time. I hope you enjoyed listening to chapter one of the Heart of a Heart Warrior. I would like to thank my co-editor, meegan Tones, for reading this chapter with me and, of course, I'd like to thank all of the wonderful authors who contributed to the book. I hope you'll join us in our book study. You can learn more about it on our website, babyheartspresscom, and I also formed a Facebook group that you can join. We are limiting the book study to only 12 people, so if you're interested in starting with us next week, don't delay signing up. I hope to see you soon and until next week, my friends, remember you are not alone.

Speaker 3:Thank you again for joining us this week. We hope you have become inspired and empowered to become an advocate for the congenital heart community. Heart to Heart with Anna, with your host, anna Jaworski, can be heard at any time, wherever you get your podcasts. A new episode is released every Tuesday from Noon Eastern Time.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

Buzzcast

Buzzsprout

That's the #Truth

Jenny Muscatell and Daniel Muscatell

The Hope and Courage Podcast for CHD Parents

Tom & Kat Hansen

Everyday Miracles Podcast

Julie Hedenborg

The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

Joanna Penn

.jpg)